Your Unofficial Europe QE Preview

Alhambra Investment Partners, LLC | Sep 12, 2019 02:30AM ET

The thing about R* is mostly that it doesn’t really make much sense when you stop and think about it; which you aren’t meant to do. It is a reaction to unanticipated reality, a world that has turned out very differently than it “should” have. Central bankers are our best and brightest, allegedly, they certainly feel that way about themselves, yet the evidence is clearly lacking.

When Ben Bernanke wrote for the Washington Post in November 2010 announcing somehow the need for a second QE despite the powerful and overwhelming success of the first, he didn’t say the goal was to maybe, arguably lower bond yield term premiums.

It was a recovery or nothing.

In other words, before we ever begin policymakers who are attempting to use R* as an excuse already admit there actually was no recovery. All R* means, to them, is that it isn’t our fault. QE didn’t fail, it couldn’t possibly have succeeded.

One of the reasons given is the proximity of interest rates to the perplexing zero lower bound; or, effective lower bound as it has been rebranded in order to make it sound more menacing. Short-term money rates cannot go below zero, therefore near to zero policymakers are handicapped in how much they can help the economy.

But that’s entirely the issue – how much can they help. Central bankers plead for how they require more altitude, a higher starting point for “accommodation” before ever getting to the unconventional policies like QE. It’s a weak argument; Ben Bernanke had 5.25% on fed funds in the summer of 2007, and he went all the way to zero (including one twelve-day stretch in January 2008 with a cumulative drop of 125 bps) without making a meaningful dent in the growing economic storm.

Are we supposed to accept that if Bernanke’s Fed had begun the crisis with a fed funds rate in the double digits only then would that have provided enough margin for that rate to fall and therefore would’ve made all the difference? That’s what these R* people are asking us to believe.

Policymakers need to have enough simple tools in their toolkits for the simple public. They now routinely make the argument that one possible reason QE maybe, might not have been as effective is because simpletons like you and me didn’t really understand it enough .

The debate now comes down to a single question; either they don’t have enough juice, or just maybe they have none. This is no trivial distinction, and it is being actively carried out in the bond market particularly at the long end – which has mainstream observers typically perplexed .

The bond market thinks central banks are out of juice and inflation will stay below target for, well, ever. The longest-dated Treasurys are priced for inflation to average 1.6% for the next 30 years, and German bonds for just 1.3% inflation.

Bond buyers know that QE is coming especially and Europe, and that in all likelihood because of this predicament central bankers will have to get creative with it, like Japan, so how could they possibly not be pricing long run success? What the bond market really thinks is beyond the ridiculous assumptions about R*. The Fed and ECB aren’t out of juice, they simply don’t have any at all. That’s just what long-term bond yields and inflation expectations are saying. It doesn’t matter where the Fed starts with Fed funds, or the ECB with its MRO-Deposit Rate corridor, there’s no money in policy even when getting to bank reserves.

And that makes all the difference. If the world runs into more monetary trouble, there’s a very broad, deep consensus about how there is nothing a central bank and its moneyless monetary policy can do to get us out. That’s what prices are really saying.

The problem for the public is merely that this deeply offends every mainstream sensibility; disbelief and bias persisting despite a mountain of unimpeachable evidence.

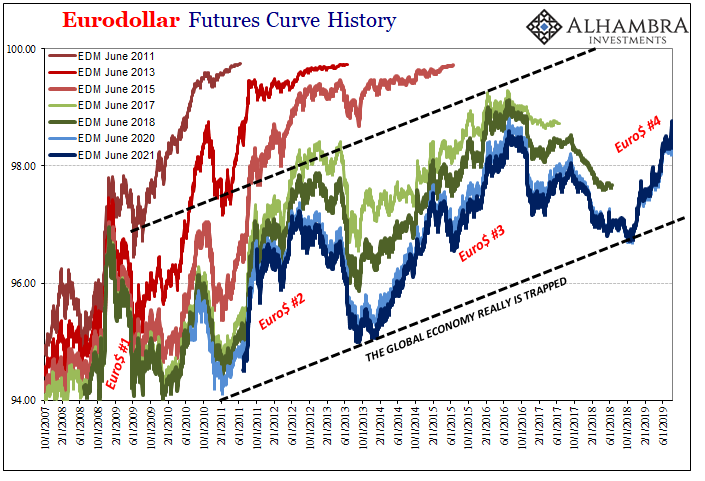

The bond market had at first given central bankers the benefit of the doubt, the opportunity to show themselves worthy of the myths and legends, but only up until the 2011 crisis (Euro$ #2). QE was new and many were willing to give it a chance; and then it proved totally ineffective (if you have to do it more than once…) as policymakers were horrified to find no matter how many bank reserves had been created the liquidity crisis spread globally anyway.

What QE accomplished was the opposite of what was intended – it established as an empirical matter how what was suspected in 2008 about how there was no money in monetary policy is actually the way things are. The banking system has reacted accordingly ever since. There’s the real R* right there.

No matter what they come out with in Europe tomorrow, or the FOMC in the coming days, it is almost certain to make very little if any effective difference in the increasingly dour long run trajectory. The problem in the economy isn’t one that any central bank can fix. The issue is their lacking toolkit, not the primitive and outdated tools inside of it.

It’s almost what Christine Lagarde meant last week when she said “I am not a fairy” and then embarrassingly run over in Argentina , more empirical proof, central banks are paralyzed by the lack of altitude; by R*, that a low R* necessitates ever more QE because no room for rate cuts.

This is backward. The lack of success with QE necessitated policymakers invent R*. The bond market simply understands this huge distinction.

The reality is this: they’d have all the space in the world for simple rate cuts if any of this actually worked. Had QE anywhere been legitimately effective there would’ve been a real, nasty bond rout worthy of epic celebration; rates much higher and normal long before today.

Instead, policymakers are left to try to make the argument that monetary policy really does work, it just didn’t. If only the consequences weren’t so monumental , we could just laugh at the absurdity of it all.

Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.