Why Speculation Is Good (Especially In The Commodities Market)

Scott Silva | Jun 27, 2012 01:49AM ET

“Greed, for lack of a better word, is good.” So said Gordon Gekko, the iconic corporate raider in Oliver Stone’s cynical 1987 film Wall Street. Michael Douglas won an Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in the film, now a classic. In the film, Gekko is ultimately imprisoned for securities fraud after years of benefiting from insider trading.

Today, many liberal legislators and left-wing politicians associate Wall Street traders and investment bankers with the criminal activities of Gordon Gekko, the fictional film character. Certainly the Occupy Wall Street protesters believe Wall Street is the seat of corporate greed and corruption. Some US Senators conflate securities fraud with speculation, frequently referring to Gordon Gekko, excess and greed in speeches designed to vilify speculators, who after all, “caused the financial meltdown” or, “caused $5.00/gal gasoline prices” with their wonton, unbridled greed.

But speculation in the commodities markets is not illegal. Nor is it immoral. In fact, speculation is integral to operation of free markets. There is a legitimate role for market speculation in efficient markets. Without market speculation, prices would be less stable and price discovery more difficult, making markets less efficient.

For example, if there were no speculators in the pork bellies market, the market would consist of producers (hog farmers) and consumers (butchers, and those who prefer to carve up their meat themselves). With just two participants in the market, the market would be thinly traded, leading to large spreads between bid and asked, which distorts prices, and makes capital investment less efficient. As a market participant, the speculator adds liquidity (risks his own capital) and provided a competitive bid which narrows the spread, making the market more efficient for all participants. Because there are two sides to a speculative trade, either the long position holder or the short position holder will benefit from price changes over time.

Usually, speculation in a particular market has a dampening effect on price volatility, but there have been periods of “irrational exuberance” where prices are bid up in exponential fashion, creating a market bubble. Speculators may participate in the development of a market bubble, as they did in the real estate market boom of 2000-2008, but it takes more than speculation to cause a market bubble. In the case of the US real estate bubble that burst in 2008, decades of easy money and government intervention in the home mortgage industry via the Community Reinvestment Act laid the foundation for the irrational boom and its ultimate bust.

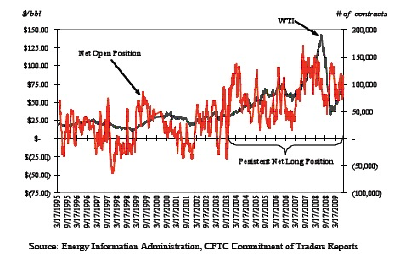

Recently, speculation has been blamed for high gasoline prices. “The oil speculators have bid up the price of oil, so you are now paying $5.00 per gallon at the pump!” complained a US Senator who proposes to ban speculators from trading oil futures. “Only producers and commercial consumers who need to hedge should be allowed to trade oil futures contracts,” say proponents of strict regulation of the oil futures markets; “Speculators are greedy, and greed is bad.” But studies show that oil prices have increased steadily since 2000, with commercial and non-commercial (speculators) holding net long into the extended bull market for oil. Even during the period of strict regulation and position limits on the commodities futures market, prior to the Commodities Futures Modernization Act, oil prices tended to climb higher year after year.

Although speculators have represented a growing percentage of open interest since 2003, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) concluded in its own investigation of the oil futures market that there is no evidence that the market was influenced by the trading behaviors of any large group of participants. In fact, CFTC chairman Walter Lukken told a committee of the U.S. House of Representatives in 2008 that CFTC analysis “did not find direct evidence that speculation was driving up (commodity) prices.” The fact is, global the oil market was tight, leading to the peak price of WTI at $147/bbl in mid 2008. The futures price was a prescient leading indicator.

If speculators did not cause the bubble in the oil market, what did? One explanation that makes sense is the weakening dollar. Because oil futures settle in dollars (or physical delivery), it takes more dollars to buy a barrel of oil, for a given supply, when the dollar is weak. Conversely, the stronger dollar purchases more barrels per dollar, driving down the price in the global market.

The value of the dollar has been trending down ever since the Federal Reserve has been printing more of the stuff in the name of US economic stimulus. It is the time-tested economic principle known as Gresham’s Law that bad money drives out good. Printing more money out of thin air debases the currency and devalues dollars in circulation.

We can see the inverse relationship of oil (West Texas Intermediate, WTI) and the US Dollar Index (USD) in the chart below. WTI peaked just as the US dollar bottomed in 2008 just as the Federal Reserve added the first $700 Billion of the $3 Trillion it would add to its balance sheet under its economic stimulus policy. The anticipated effect of spurring the economy into robust recovery has proved elusive. But there are unintended negative consequences of the Fed’s money printing spree, which include higher prices for commodities. As we know from Milton Freidman and the recently departed Anna Schwartz, may she rest in peace, inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.

We also know that the price of gold reflects the strength of the dollar. The dollar’s drift from 2002 to 2008 helped propel the price of gold up over $1200/oz. Of course, there are other factors that contribute to gold’s rise. Gold is the traditional safe-haven asset that investors seek out in times of economic uncertainly, turmoil and war. Gold has intrinsic value, and it acts as a store of value. Unlike fiat currency, gold maintains its value and is recognized as viable collateral for transactions in markets around the world.

Today, oil prices have subsided a bit from the highs of over $110/bbl earlier this year. WTI is now trading down below $80/bbl with no added supply. Some analysts believe that the war premium has been wrung out of the price. Iran is no longer openly threatening to close the Strait of Hormuz. Maybe so, but the primary cause is softer demand. Double dip recession in Europe, a slowdown in China and the continuing slow-motion, no-growth, jobless recovery in the US has dampened demand for energy. And by the way, the Large Speculators have been cutting back their long positions on WTI and adding short positions; last week’s Commitment of Traders report showed bullish sentiment for oil has dropped to 63% down from 96% in February when WTI was trading near $110/bbl. No one seems to complain about speculators when prices go down.

Gold is also trading below $1600/oz. But more poor US economic data is coming for sure, and the Fed will jump in with more quantitative easing, adding more to its balance sheet which will further devalue the currency. So, in today’s market, take a page from Gordon Gekko’s playbook. Buy, buy, buy gold. Because, as we all know, “Greed is good.”

Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.