Why High Oil Prices Are Now Affecting Europe More Than the U.S.

Gail Tverberg | Mar 05, 2012 03:05AM ET

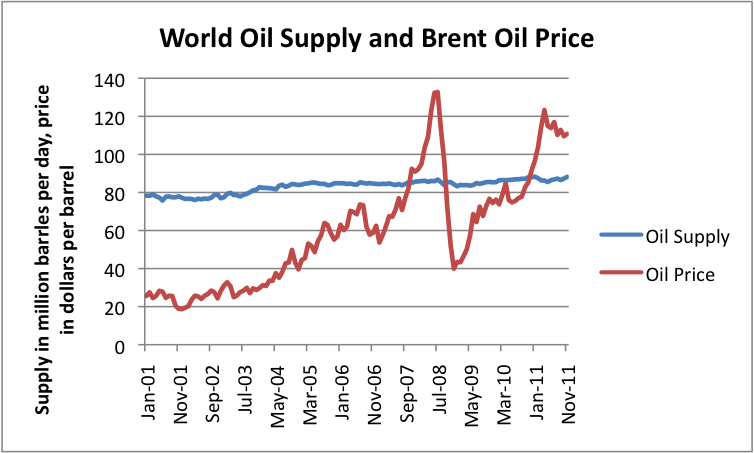

The world is presently sharing a limited supply of oil. When oil prices rise, oil production doesn’t rise very much, if at all.

Figure 1. Brent oil spot price and world oil supply (broadly defined), based on EIA data.

The issues then become: Which buyers get the oil? What uses get priced out of the market? Which countries are disproportionately affected?

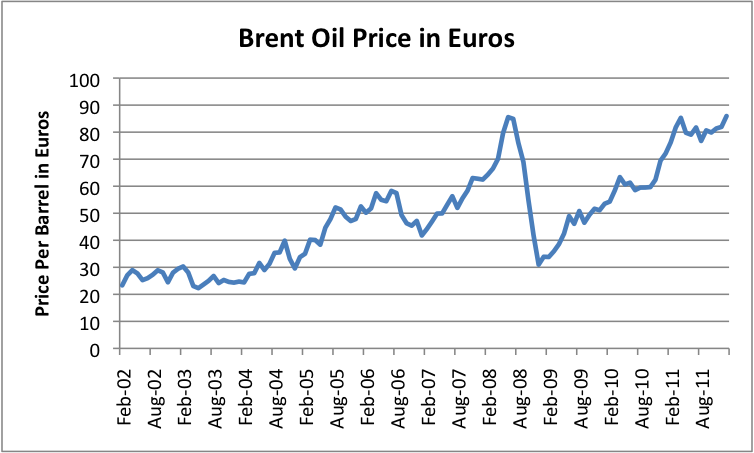

It seems to me that this time around, Europe, and in particular the Eurozone, is the area of the world getting hit the hardest by high oil prices. Part of this has to do with the relative level of the Euro and the US dollar. If we look at the price of Brent oil (a European oil) in Euros (Figure 2), we find that prices now are as high as now as they were in mid-2008.

Figure 2. Dated Brent average monthly oil prices, expressed in Euros, based on IndexMundi data.

The situation in the United States is fairly different. The dollar-Euro comparison works more in the favor of the US, so that the rise of Brent in US dollars has been smaller this time than in 2008. In addition, refineries in the United States have been fortunate enough to purchase quite a bit of the oil they buy at prices below that of Brent. The issue leading to lower prices in the United States is lack of pipeline capacity, creating a bottleneck for shipping oil to Gulf Coast refineries.

Figure 3. Comparison of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Dated Brent Oil Prices, expressed in US Dollars. Data from IndexMundi.com.

Figure 3 shows two different benchmark prices of crude oil in the United States: Brent and West Texas Intermediate (WTI). Oil that is imported to the United States from Europe and Africa can be expected to follow Brent prices, as will oil that is produced along the Gulf Coast, and has convenient access to Gulf Coast refineries. Oil that comes from the North, such as crude from Canada and the Bakken, is subject to pipeline limitations, and its price will tend to follow that of WTI (or trade for an even lower price than WTI). Oil purchased by US refineries thus reflects a blend of WTI and Brent prices, and perhaps some lower ones as well. Based on Figure 3, it is clear that the current prices are far below the 2008 price peak, quite unlike the situation shown in Figure 2 for Europe, with Brent priced in Euros.

Availability of Locally Produced Oil versus Imports

Europe’s oil production has been declining since about 2002.

Figure 4. Europe "all liquids" oil production (including biofuels and natural gas liquids) based on EIA data. 2001 estimated based on 11 month data.

This decline in oil production by itself has a negative impact–fewer jobs and less tax revenue.

In comparison, oil production in North America (Figure 5, below) has been much more level, and has even been rising somewhat recently. A rise in US and Canadian production has helped offset a decline in Mexican production. Since the amounts shown are “all liquids,” the amounts shown include biofuels and natural gas liquids, which are oil supply extenders, but are not true “crude oil.”

Figure 5. North American "All Liquids" production, including crude oil, natural gas liquids, and biofuels, based on EIA data. 2011 estimated based on 9 months data.

An even more important issue, though, is that European oil does not benefit all European nations. Instead, it is the countries that extract the oil that benefit, primarily Norway and the United Kingdom. Countries that do not extract the oil must import any oil they use.The countries that import oil generally import natural gas as well, at prices that are partially tied to the price of oil, so they are hit doubly hard.

Paying for these high-priced imports reduces the amount that residents of these countries can be spend on other discretionary goods, and contributes to a tendency toward recession. Furthermore, if a country is not producing oil and natural gas itself, it does not get the offsetting benefits of additional jobs in the oil and gas sectors.

Figure 6. Percent of Energy Consumption from Imported Oil and Gas, for selected countries, based on BP Statistical Data.

Figure 6 shows that the PIIGS countries are all very heavy importers of oil and natural gas. In fact, they are the five countries listed on the on the left of Figure 6, with the highest level of imports. When oil prices rise, these countries are disproportionately affected, because, for example, tourists can no longer afford vacations in their countries. Their debt problems are in part tied in to high oil prices, since when workers are laid off, a country collects less in taxes and needs to pay more in benefits to unemployed workers.

The US has a relatively low level of imported oil and gas imports compared to most European countries. This occurs partly because of its significant use of coal and nuclear, and also because of the large size of its own oil and gas production.

Another factor that helps the United States in dealing with high energy prices is its current low price of natural gas, relative to that of Europe and Japan (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Natural gas prices in the United States, Europe, and Japan, based on World Bank Commodity Price Data (pink sheet)

US natural gas prices are currently extremely low, because of an imbalance between natural gas supply and demand. These low prices for natural gas mean that the cost of home heating and of electricity are now lower than they have been historically in some parts of the country. These lower heating and utility costs help offset the rising price of oil. The issue of why US natural gas prices are so low will be the subject of another post in the near future.

The low price of natural gas also makes the cost of refining heavy oil less expensive in the United States than elsewhere, because natural gas is used by complex refineries that refine heavy oil , both as a feedstock, and to fire the furnace that heats the crude oil. This makes the United States a sought out destination for refining heavy crude oil, and helps add jobs to the US economy. For example, nearly half of crude oil imported from Mexico to the US is exported back to Mexico as oil products, according to EIA data. EIA data also shows that we import crude and export a smaller amount of products back to Canada, Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela. The low price of natural gas is thus a reason US product exports, such as diesel and gasoline, have been increasing recently, even though the United States continues to be a big importer of crude oil.

Nuclear Makes a Difference

The reason why Japan, Germany, Switzerland, and France have as low imported oil and gas dependencies as they do (Figure 6, above) is because they historically have all had very significant nuclear energy installations. If the amount of nuclear energy production is added to oil and gas imports, the resulting ratios are more like that of the PIIGS countries, with imported oil and gas dependencies exceeding 65% of total energy consumption (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Effect of combining nuclear energy consumption with current imported oil and gas consumptions, as a percentage of total energy consumption. (Based on BP Statistical Data.)

If countries with nuclear programs decide to discontinue them, it will be a challenge to find other sources of energy with which to replace the nuclear. While LNG production is increasing, it is doubtful that it can increase enough to match everyone’s needs. Many are hopeful that wind and solar will work as substitute, but this is far from proven. Scale up tends to be very slow.

What is Ahead for the Eurozone?

The Eurozone includes 17 countries that have adopted the Euro. It does not include the major oil-producing countries of Norway and the United Kingdom, and it does not include Switzerland.

Figure 9 (below) shows that the oil supply situation for the Eurozone is very poor. It is pretty much entirely dependent on imports.

Figure 9. Countries of Eurozone, oil consumption of Eurozone (black line), and oil imports of Eurozone, in graph from Energy Export Databrowser.

Figure 10 shows that the natural gas supply situation is only a bit better:

Figure 10. Eurozone natural gas consumption (black line), production (grey area above mid-line), and imports (red area below mid-line). Graph from Energy Export Databrowser.

With no oil supply, and a modest but declining natural gas supply, Eurozone countries can expect to spend more money on oil and gas imports in the future, assuming that they can get these products when they want them.

The Eurozone has the additional problem of having a common currency, but debts entered into by individual countries. Individual countries cannot issue currency. If a particular country would benefit by having their currency have a higher or lower value, there is nothing that can be done about the situation, because the Euro is at a common level for all. So it is easy to reach the situation we are in today, with Greece and a number of other countries near debt defaults, when oil prices are high.

The question going forward, besides the debt problems, is how the Eurozone’s energy problems will be solved. After the Fukushima accident, many are questioning whether nuclear is really a good option. Another option is coal, although it is problematic from a CO2 point of view. There is some coal in the Eurozone, but less than is currently consumed, and extraction is declining each year:

Figure 11. Coal production (grey area above midline) and coal imports (red below midline). Graph from Energy Export Databrowser.

The countries that have banded together in the Eurozone are in a weak position because of their poor energy supply situation. There has been a great deal of work done on wind and solar in the Eurozone, but these still comprise only a small percentage of energy consumption. While many would argue that “renewables” are the way of the future, the fact remains that the vast majority of energy is not from renewables today, and the high price of oil and gas is already causing a problem.

Various policies have been put in place to curb fossil fuel use, but Eurozone countries remain very dependent on fossil fuels. With world oil supply flat, and other parts of the world growing more rapidly than the Eurozone, the Eurozone will need to make major cuts in oil usage in the years ahead. One way this might happen is by one or more countries dropping out of the Eurozone, going back to their old currencies, and letting their currencies devalue. With devalued currencies, these countries will be better able to compete for tourist trade and for export markets. This would leave the remaining Eurozone countries in a less competitive position, however, and make it advantageous for other Eurozone countries to drop out. This scenario would seem to lead to the end of the Eurozone and many debt defaults.

Are Other Countries Better Off for the Long Run?

While the United States, United Kingdom, and Japan would seem to be in better shape, this is not necessarily the case for the long run.

In part, the long run is different because individual situations are temporary. Japan is vulnerable now, with most of its nuclear generating stations down, and the need for more imports of some sort to balance the situation. The United States for now has lower oil prices due to pipeline problems, but these will eventually be solved.

In part, the long run can be expected to be different because problems of one country affect other countries. If there are debt defaults in PIIGS countries, these are likely to affect banks and insurance companies around the world. Also, almost every country has a debt problem, unless economic growth returns. If the nations of the world are sharing a virtually flat oil supply, it is difficult for very much economic growth to take place, because high oil prices reduce funds available for other purposes. Need for greater energy resources is likely to lead to more resources of all types (people, capital, and raw materials) being devoted to creating energy of some type (high priced oil and gas, or substitutes), leaving less for other economic sectors, such as those making discretionary goods.

So in the end, it may not matter which countries were first and most affected by limited oil supply and high oil prices. It will be all of us that feel the impact.

Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.