Understanding Negative Interest Rates

Sober Look | Apr 12, 2016 02:12AM ET

When the central banks of three European countries and the European Central Bank (ECB) itself introduced negative interest rates (NIR) in mid-2014, many considered it be a temporary measure, a new experiment in monetary policy. But when the Bank of Japan did the same in January 2016 and when the ECB pushed rates further into negative territory in March 2016, the international investment world stood up and took notice. Policy makers are now prepared to test this unconventional technique in an effort to stimulate growth and tackle deflation.

The financial press is full of articles on the dangers of this policy. These unconventional moves have provoked a lot of criticism, especially from the banking community who fear a strangulation of normal banking activities. A lot has been written about the dangers that NIR pose to the stability of banks and to the possible harm to savers and investors alike. This article is an attempt to put the whole question of NIR into a more balanced perspective. To begin with, it is important to have some background to why and how NIRs have come to characterize so much of government debt.

How Pervasive are NIRs?

According to the JP Morgan international bond index, approximately 25% of its government bond index is in negative territory (see Chart 1, below). More importantly, the size of that market has grown rapidly and dramatically from zero in mid-2014 to more than US$6 trillion today.

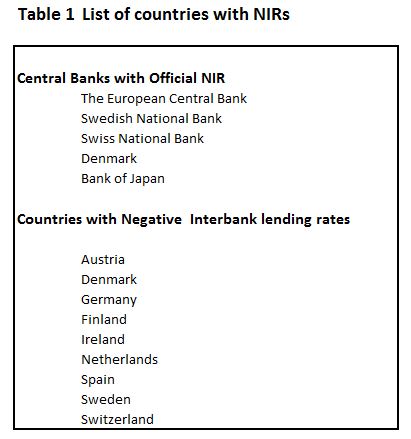

Table l, below, lists the countries whose official central policy calls for NIRs and whose interbank lending rates are negative. The interbank lending rates are a measure of how willing commercial banks are prepared to lend to each other on a very short term basis. In Europe, alone, nine countries' interbank lending rates are in negative territory.

Initially, the sub-zero debt instruments were confined to the very short end of the yield curve. However, as Chart 2, below, reveals, NIRs have been extended to the middle and longer ends of the yield curve. In Germany, sub-zero rates extend up to five years and, in Japan, negative rates extend out to 10 years - the Japanese 30-year bond trades at a mere 0.50 percent. It should be emphasized that, although the central banks set only bank policy rate, the marketplace determines all rates along the yield curve from 2-years to 30-years. Clearly, the goal of lowering long-term interest rates has been achieved in Europe and Japan. It will take an extraordinary shift of inflationary expectations to eliminate negative rates this far out on the yield curve.

| Source: http://www.bloombergview.com , March 18,2016 |

In the case of non-Euro countries like Sweden, Denmark and Switzerland, these countries adopted a policy of NIR to hold down the external value of their domestic currencies. Money was flowing into these nations' coffers from the Euro countries, putting undue upward pressure on their domestic currencies to the detriment of their trade and capital balances. Despite the fact that the Federal Reserve has signaled that it wants to raise the short-term rates as part of its efforts to `` normalize`` monetary policy , Janet Yellen said last November that certain economic conditions could put negative rates "on the table". Never say never.

NIR bonds are not solely confined to the government sector. Recently, such blue chip European corporations as Nestle (SIX:NESN), the energy corporation EDF (PA:EDF), Royal Dutch Shell (LON:RDSa) and drug makers, Sanofi (PA:SASY) and Novartis (SIX:NOVN), have been trading at sub-zero rates for more than a year. Chart 3, below, sets the dramatic drop in investment grade corporate bond yields since the announcement of NIRs by the ECB in 2014.

| Source: FT |

What Gives Rise to Negative Rates?

One way to approach this question is to consider the nature of a " liquidity trap'. In describing monetary conditions in the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes coined the term "liquidity trap" in which declining interest rates fail to promote greater consumer borrowing and spending. The demands for money from consumers and business owners are no longer sensitive to the drop in interest rates.

Another way to look at this phenomenon is to consider that money is essentially trapped in the financial system—even at zero rates of interest, the economy fails to show any signs of meaningful economic growth. We have not seen this situation since the 1930s when Keynes first labelled it. So, it is quite a shock to the policy makers that even a zero rate of interest did not stimulate borrowing and spending . Now, some central banks have resorted to introducing unconventional means such as NIRs.

Economists have cited various reasons for a liquidity trap and some are featured in today's environment:

- Expectation of deflation. In Japan an entire generation since the 1989 financial and property market crash has experienced deflation; consumers feel no urgency to go out and spend now, since they expect prices to fall further in the near future. In the EU, the debt crisis of 2012 has ushered in a period of austerity, accompanied by expectations of stagnation and further deflation.

- Credit tightening. Following the 2008 banking crisis, banks worldwide have had to raise capital in order to improve their balance sheets ; they are reluctant to lend, regardless of the creditworthiness of the borrowers.

- Savings rate increases. A pessimistic outlook will lead to consumers increasing their savings as a precaution; the debt crisis in Europe has prompted consumers and government to hold back on expenditures as part of an overall austerity policy. Savings as share of GDP is relatively high in countries featuring NIRs.

Who Buys Negative Interest Bonds?

So, who would buy a NIR bond? One category includes institutional investors who have to own government bonds, regardless of their returns. Central banks own bonds as part of their foreign exchange reserve positions. Insurance companies and pension funds need to hold bonds as part of their reserve requirements and to match long-term liabilities. And, commercial banks need bonds to meet liquidity requirements.

A second group includes speculative investors who expect bond yields to fall further in response to other monetary policy shifts, eg. the ECB announcing an extension of its bond buying programme (QE). Or, these investors anticipate a currency appreciation that more than offsets the loss due to negative yields. Many foreign investors buy Japanese bonds with the expectation that the yen will appreciate beyond the loss in yield. In fact, the yen has been strengthening against the US dollar over the last couple of months, since the BoJ introduced its NIR policy.

A third group of investors have no alternatives. The security and transactional cost of holding very large cash balances can be very expensive compared to a small loss from an NIR bond. Finally, government bonds, even if yielding negative returns, are considered as a relatively cheap and safe haven in the time of market volatility.

How do NIRs Work?

Let's clear up a few misconceptions.

First, the negative rates are really aimed at the institutional investor, eg. pension funds, large corporations. The retail investor is not the target and has not been directly impacted; rates may be low, but there are positives for the retail saver.

Second, no government is forcing an investor to accept negative rates. After all, the investor can seek higher returns in more risky assets. In fact, that is precisely the desired goal of the policy makers. However, given what happened in the 2008 financial crisis, it is entirely rational for a risk-averse investor to buy a highly liquid and safe investment to protect against a future financial crash. For example, foreign banks have approximately 17 billion Swiss francs on deposit in the Swiss central bank at negative rates as a way of protecting capital and having access to liquidity; both are prudent corporate policies.

Third, Japan, for example, cut its deposit rate on cash held at the BoJ by the commercial banks that exceeded the legally required reserves; banks often find themselves with cash reserves in excess of their banking requirements and those excess reserves are normally lent to the central bank. The BoJ wants to encourage the commercial banks to make these excess reserves available for lending to consumers and businesses. The BoJ made it clear that the aim is to make more money available at lower costs to stimulate growth and inflation.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) recently examined the how NIRs are implemented within Europe, the area with the most experience to date. The BIS concluded that:

- NIRs work through the money markets and other interest rates in the same way that positive rates do; no disruptions were identified.

- The one major exception is that banks have been reluctant to pass negative rates to their retail customers; the fear was that negative rates would lead to major deposit withdrawals.

- The drop in longer-term interest rates has taken place at the same time as ECB adopted a programme of purchasing government debt ( QE ); so, it is difficult to isolate the impact of negative rates from that of its bond buying programme.

The BIS concludes that ``looking ahead, there is great uncertainty about the behaviour of individuals and institutions if rates were to decline further into negative territory or remain for a prolonged period``. Nevertheless, the policy, to date, has not harmed the banking system nor has it disrupted savings patterns (1).

Are NIRs necessary?

NIRs are part of a long list of unconventional monetary policy moves which include purchases of government bonds, purchases of mortgages and other asset-backed securities,forward guidance and currency devaluations. To date, these efforts have failed to stimulate growth. Had these governments adopted expansionary fiscal policies, there would not be the need for so many unconventional policy moves, of which the latest is NIRs. In a sense, governments have been struggling to shake off slow growth and deflation with one hand tied behind their backs.

Summing up, NIRs have permeated the banking world, especially in Europe and Japan and by all accounts this is not just a temporary condition. Subzero rates now extend into the longer end of the yield curve as the demand for government debt continues to remain strong. Reasons vary by investor groups as to why they participant in what is , on the surface, a counter-intuitive investment strategy. The strategy may not have been necessary had governments adopted more expansionary fiscal policies. Nevertheless, the jury remains out regarding the longer term effectiveness of NIRs.

(1) BIS `How have central banks implemented negative policy rates? ", M. Linnermann and A. Malkhozov, March 2016

by Norman Mogil

Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.