The Warning Embedded Within The Interest Rate Fallacy

Alhambra Investment Partners, LLC | Jun 29, 2016 02:52AM ET

On November 4, 2010, then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke wrote his infamous oped for the Washington Post “welcoming” the world to a second round of quantitative easing. The very fact that there was a second iteration belied the whole point of “quantitative”, but the mistakes about “easing” have proven far more problematic. There wasn’t anything new or unusual in his article, just the normal appeal to “easier financial conditions” provided by his monetary “accommodation.”

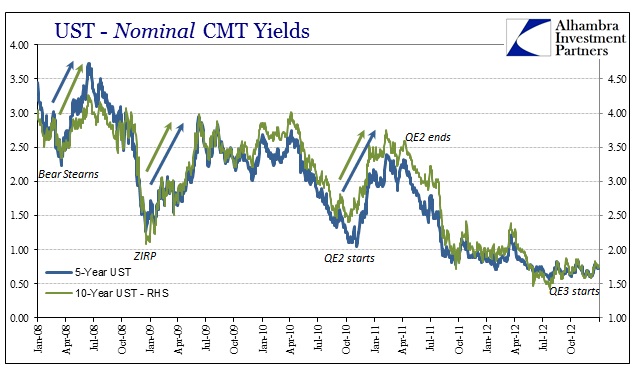

Despite intending to aid the economy by reducing rates to make borrowing less relatively expensive, interest rates actually rose from that point forward. The yield for the 5-Year US treasury hit its lowest level to that point on the day the oped was published; jumping from only 1.04% on November 4 all the way to 2.39% by early February 2011. The 10-Year UST had turned around even sooner in anticipation of further FOMC action, but largely followed the same pattern. The media was immediately confused and remained in that state as treasury yields and interest rates continued to behave seemingly opposite to how they were supposed to; as was Bernanke himself as he would admit some years later .

For example, in the US, ten-year Treasury yields have fallen from around 3 percent at the end of 2013, to about 2.5 percent during the summer of 2014, to around 1.9 percent today. The recent renewed decline was unexpected by most observers, including me. Why are longer-term interest rates so low? And why have they fallen even further recently, despite signs of strength in the US economy?

This was not the first time, however, that bond markets and interest rates had responded in this fashion. ProShares Ultra 7-10 Year Treasury (NYSE:UST) yields had fallen in early 2008 until the day Bear Stearns had failed; and from that point until June of that year, interest rates rebounded significantly. At the end of 2008, after all the panic and fear, from the day the Fed announced ZIRP until the middle of June 2009 (through the early portion of QE1) rates again rose sharply.

In each of these three instances, what we find is actually a positive response to central bank policy – only short-lived each time. The bond market wasn’t defying QE or Fed “stimulus” rather it was expecting that all of it was going to work and pricing such that it would. Rising rates (from a low starting point) in bond markets is a sign of anticipated health and sustained growth. Thus, when rates began rising in the autumn of 2010 it was in the belief that Bernanke and the FOMC knew what they were doing even though the prior two times the market had taken “stimulus” on faith had turned out very badly.

The third time, of course, did, too. In contrast to the bond market reaction to QE2, there was very minimal response to QE3; fool me thrice, shame on economics. There is a determined difference between short run interest rates and long-term interest expectations. Though central banks purport to follow something like Knut Wicksell’s natural rate theory, in reality they have changed it around such that everything is viewed via the “demand” side; and thus nothing actually makes sense including the behavior of market interest rates.

This is what Milton Friedman called the interest rate fallacy, and it indeed refuses to die. We can tell what monetary conditions are in the real economy, as opposed to financial liquidity, though the two can be linked, by the general level of interest rates. When money is plentiful, interest rates will be high not low; and when money is restricted, interest rates will be low not high. The reason is as Wicksell described more than a century ago:

[The natural rate] is never high or low in itself, but only in relation to the profit which people can make with the money in their hands, and this, of course, varies. In good times, when trade is brisk, the rate of profit is high, and, what is of great consequence, is generally expected to remain high; in periods of depression it is low, and expected to remain low.

When nominalprofits are expected to be robust, holders of money must be compensated for lending it out by higher interest rates. Thus, the same holds for inflationary circumstances, where nominal profits follow the rate of consumer prices. During the Great Inflation, interest rates weren’t low at all, they were through the roof well into double digits and higher by 1980. At the opposite end in the Great Depression, interest rates were low and stayed there because, as Wicksell wrote, the rate of profit was low and was expected to be low well into the future. High quality borrowers were given as much money as they could want while the rest of the economy was deprived of funds; liquidity and safety being the only preferences in what sounds entirely familiar.

While the wholesale monetary system is different in format and varied in complexity, functionally it amounts to the same tendencies. That is why interest rates have behaved as they did; when the market viewed “stimulus” as stimulus, rates reacted in accordance with this “income effect” where successful completion was supposed to lead to plentiful money and economy in the near future – rising interest rates. And each time the market was sorely disappointed to find out that what the Fed’s “stimulus” actually amounted to was far from functional money, and therefore didn’t actually stimulate anything other than central banker self-regard (so many “heroes”).

This view on interest rates provides us with some insight as to why the events of 2011 were a seemingly permanent alteration in both banking (eurodollar basis) and the global economy. QE2 was supposed to be a large expansion of money, yet there was almost immediately another crisis where it was clear that even short-term liquidity had never been repaired let alone restored (a global problem again). If the short-term liquidity expectations surrounding QE (and really bank reserves) were all wrong, what did that suggest about monetary assumptions in regard to the real economy?

It means, unequivocally, that low rates are not stimulative at all, rather they are indicative of monetary contraction. Another way of saying that in mainstream terms is if a central bank “needs” to stimulate year after year after year it isn’t actually stimulating anything, it is being slowly strangled by the same monetary noose in sympathy with the real economy. The real economy loses function and activity while the central bank loses (rightfully) credibility.

Again, this shift in perception dating back to 2011 is important as it shows up all over the world. Before that point in later 2011, the recovery seemed at least possible if visibly insufficient and so it was plausible that policies like QE might work if given enough time and emphasis. After 2011, bank reserves were downgraded to fantasyland, leaving the eurodollar world without any legitimate form of financial backing; high risk, low (no) reward. Banks left and the global economy stagnated even though it had never recovered from the Great Recession.

The resulting paradigm shift in eurodollar money has been an equivalent paradigm shift in the economy. No matter what central banks attempt or propose, they noted last week , some indeterminate secular stagnation so much as eurodollarstagnation.

Unfortunately, the answer is not to increase the eurodollar supply because there is simply no way to do so. The eurodollar must be replaced, but our central bank “heroes” are busy instead coming up with ways to explain why QE didn’t fail (it was the economy’s fault). The end result is thus the familiar social and political upheaval that accompanied the earlier extremes in monetary imbalance. Hopefully it will be far more like the transition to the 1980’s rather than that of the 1940’s. The longer this takes, however, the likelihood of the former, I fear, decreases, while the potential for the latter grows. It might be tilted in that direction anyway since there are vast differences between monetary contraction and depression versus runaway inflation. As bad as the late 1970’s was in economic as well as financial terms, it just doesn’t compare to periods of prolongedidleness and deprivation.

From money curves to fixed income yields, from dollars to yen to euros, global markets are issuing a heightened warning of a very bleak future. Is anybody listening? Central bankers aren’t.

Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.