Share Count Confusion: Dilution, Employee Options And Multiple Share Classes!

Aswath Damodaran | Jul 26, 2018 12:58AM ET

In my last post , just about four weeks ago, I valued Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA), and as with all of my Tesla valuations, I got feedback, much of it heated. My valuation of Tesla was $186, in what I termed my base case, and there were many who disputed that value, from both directions. There were some who felt that I was being too pessimistic in my assessments of Tesla's growth potential, but there were many more who argued that I was being too optimistic. In either case, I have no desire to convert you to my point of view, since the essence of valuation is disagreement. In the context of some of these critiques, there was discussion of how my valuation incorporated (or did not incorporate) the expected dilution from future share issuances and what share count to use in computing value per share. Since these are broader issues that recur across companies, I decided to dedicate a post entirely to these questions.

Share Count and Value Per Share There was a time, not so long ago, when getting from the value of equity for a company to value per share was a trivial exercise, involving dividing the aggregate value by the number of shares outstanding. Value per share = Aggregate Value of Equity/ Number of Shares outstanding This computation can become problematic when you have one or more of the following phenomena:

- Expected Dilution: As young companies and start-ups get listed on public market places, investors are increasingly being called upon to value companies that will need to access capital markets in future years, to cover reinvestment and operating needs. To the extent that some or all of this new capital will come from new share issuances, the share count at these companies can be expected to climb over time. The question for analysts then becomes whether, and if yes, how, to adjust the value per share today for these additional shares.

- Share based compensation: When employees and managers are compensated with shares or options, there are three issues that affect valuation. The first is whether the expense associated with stock based compensation should be added back to arrive at cash flows, since it is a non-cash expense. The second is how to adjust the value per share today for the restricted shares and options that have already been granted to managers. Third, if a company is expected to continue with its policy of using stock based compensation, you have to decide how to adjust the value per share today for future grants of options or shares.

- Shares with different rights (voting and dividend): When companies issue shares with different voting rights or dividends, they are in effect creating shares that can have different per-share values. If a company has voting and non-voting shares, and you believe that voting shares have more value than non-voting shares, you cannot divide the aggregate value of equity by the number of shares outstanding to get to value per share.

Note that while none of these developments are new, analysts in public markets dealt with them infrequently a few decades ago, and could, in fact, get away with using short cuts or ignoring them. Today, they have become more pervasive, and the old evasions no longer will stand you in good stead.

Expected Dilution The Change: An investor or analyst dealing with publicly traded companies in the 1980s generally valued more mature companies, since going public was considered an option only for those companies that had reached a stage in their life cycle, where profits were positive (or close) and continued access to capital markets was not a prerequisite for survival. Young companies and start-ups tended to be funded by venture capitalists, who priced these companies, rather than valued them. In the 1990s, with the dot com boom, we saw the change in the public listing paradigm, with many young companies listing themselves on public markets, based upon promise and potential, rather than profits or established business models. Even though the dot com bubble is a distant memory, that pattern of listing early has continued, and there are far more young companies listed in markets today. An investor who avoids these companies just because they do not fit old metrics or models is likely to find large segments of the market to be out of his or her reach.

The Consequence: If you are valuing a young company with growth potential, you will generally find yourself facing two realities. The first is that many young companies lose money, as they focus their attention on building businesses and acquiring clientele. The second is that growth requires reinvestment, in plant and equipment, if you are a manufacturing company, or in technology and R&D, if you are a technology company. As a consequence, in a discounted cash flow valuation, you can expect to see negative expected cash flows, at least for the first few years of your forecast period. To survive these years and make it to positive earnings and cash flows, the company will have to raise fresh capital, and given its lack of earnings, that capital will generally take the form of new equity, i.e., expected dilution, which, in turn, will affect value per share.

The Right Response: If you are doing a discounted cash flow valuation, the right response to the expected dilution is to do nothing. That may sound too good to be true, but it is true, and here is why. The aggregate value of equity that you compute today includes the present value of expected cash flows, including the negative cash flows in the up front years. The latter will reduce the present value (value of operating assets), and that reduction captures the dilution effect. You can divide the value of equity by the number of share outstanding today, and you will have already incorporated dilution.

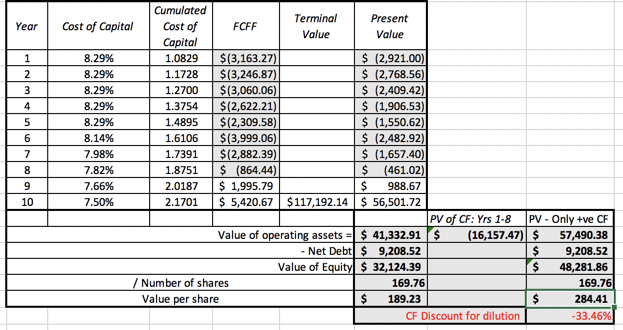

I know that it sounds like a reach, but let me use my base case Tesla valuation to illustrate. In the table below, I have my expected cashflows for the next 10 years, with the terminal value in year 10.

The present value of the expected cash flows across all 10 years is $41,333 million, and netting out debt and adding back cash, yields an equity value of $33,124 million; the value per share is $189.23. However, this value includes the present value of expected cash flows from years 1 through 8, which are negative in my forecast,s and have a present value of $16,157 million. If these cash flows had not been considered, the value of the operating assets would have been $57,490 million and the value of equity would have been $48,282 million, a value per share of $284.41. In effect, we have applied a 33.46% discount to value, for future dilution.

Implicitly, I am assuming that the firm will fund 88.06% of its capital needs with debt, consistent with the debt ratio that I assumed in the DCF, and that the shares will be issued at the intrinsic value per share (estimated in the valuation), with that value per share increasing over time at the cost of equity. That may strike some as unrealistic, but it is the choice that is most consistent with an intrinsic valuation. If Tesla is able to issue shares at a higher price (than its intrinsic value), we will have over estimated the value per share, and if it has to issue shares at a price lower than its intrinsic value, we will have under estimated value. There is one final reality check. While we have implicitly assumed that Tesla will have access to capital markets and be able to raise capital, there is a chance that capital markets could shut down or become inaccessible to the firm. That risk is not in the discounted cash flow valuation and has to be brought in explicitly in the form of a chance of failure. In my base case valuation, it is one of the reasons that I attached a chance of failure (albeit a small one of 5%) to the company.

A Viable Alternative: There is an alternative approach, where you forecast the number of shares that will be issued in future years to cover the negative cashflows, and count them as shares outstanding today. If you use this approach, you should set the cash flows for the negative cash flow years to be zero. The peril in this approach is that there is a circularity that can cause your valuations to become unstable, since you will need to forecast a price per share in future years to get an estimate of value per share today. To illustrate this process, assume that you believe that the issuance price for Tesla for the new shares will be $200, with a price appreciation of 9% a year for the next 8 years. The table below computes the new shares that will need to be issued each year, assuming that 88.06% of capital comes from equity, and the dilution that will result as a consequence.

Note that, with the assumptions about the issuance price of $200, Tesla will issue 69.35 million shares over the next eight years. Adding that to the current share count of 169.76 million shares yields total shares outstanding of 236.85 million shares. If you set the cash flows in years 1-8 to zero and compute the value of equity, you arrive at a value of equity of $48,282 million, which can be divided by the 239.11 million shares to arrive at a value per share of $201.92. This is slightly higher than the value that I obtained in the cash flow approach, but it is partly because I have assumed an issuance price that is higher than the intrinsic value.

But Never Do This: Reviewing the two approaches, you can either incorporate the present value of the negative cash flows into the value of operating assets today and use the current share count, in estimating value per share, or you can try to forecast expected future share issuances and divide the present value of only positive cash flows by the enhanced share count to get to value per share. You cannot do both, because you are then reducing value per share twice for the same phenomenon, once by discounting the negative cash flows and including them in value and then again by increasing the share count for the shares issued to cover those negative cash flows.

Share Based Compensation (SBC) The Cause: Over history, businesses have used equity to compensate employees, either to align incentives or because they lack the cash to pay competitive wages. That said, the use of share based compensation exploded in the 1990s due to two reasons. The first was an ill-conceived attempt by the US Congress to put a cap on management compensation, while not counting options granted as part of that compensation. Not surprisingly, many firms shifted to using options in compensation packages. The second was the dot com boom, where you had hundreds of young companies that had sky high valuations but no earnings or cash flows; these companies used options to attract and keep employees. Aiding and abetting these firm, in this process were the accountants, who chose not to treat these option grants as expensed at the time they were granted, and thus allowed companies to report much higher income than they were truly earning.

The Consequence: As companies shifted to share based compensation, there were two side effects that analysts had to deal with, when valuing them. The first was the drag on per-share value created by past option and share grants to employees, with options, in particular, creating trouble, since they could create dilution, if share prices went up, but could be worthless, if share prices dropped. The second was the question of how to factor in expected option and share grants in the future, since the value of these grants would be affected by expected future share prices. As with the dilution question, analysts faced a circular reasoning problem, where to value a share today, you had to make forecasts of the value per share in future years.

The Right Response: To deal with share based compensation correctly, you have to break it down into two parts:

1. Past option and share grants: If you own shares in a company, the shares and options granted by the firm in prior years to employees represent claims on the equity, that reduces your value per share. The shares issued in the past are simple to deal with, since adding them to the share count will reduce the value per share today. The fact that employees have to vest (which requires staying with the firm for a specified time period) and that the shares have restrictions on trading can make them less valuable than unrestricted shares, but that is a relatively small problem. The options that have been granted in the past are a bigger challenge, since they represent potential dilution, but only if the share price rises above the exercise price. Option pricing models are designed to capture the probabilities of this happening and can be used to value options, no matter how in or out of the money the options are. In an intrinsic valuation, you should value these options first (using an option pricing model) and net the value out of the estimated value of equity, before dividing by the existing share count :

- SBC Adjusted Value per share = (DCF Value of Equity - Value of Employee Options)/ Share count today including restricted shares

Note that the shares that will be created if the options get exercised should not be included in share count, in this approach, since that would be double counting.

2. Expected future grants: To the extent that a company is expected to continue to compensate its employees with options or restricted shares in future years, the most logical way to deal with these grants is to treat them as expenses in future years, and reduce expected income and cash flows. Rather than grapple with expected future share prices, you should estimate the expenses (associated with SBC) as a percent of revenues, and use that forecast as the basis for expenses in the future. Until accounting came to its senses in 2004 and required companies to expense share based compensation at the time of grant, this was an onerous exercise for analysts, since it required estimating the value of option and share grants in past years to get historical numbers on the value of SBC grants. With the prevalent accounting rules in both GAAP and IFRS, the earnings that you see for companies should already be adjusted for SBC expenses and reported income should therefore give you a fair basis for forecasting. (The operating and net margins that I report by sector, on my website, are margins after stock based compensation expenses). At first sight, it may seem like double counting to lower future earnings because you expect option and share grants in the future, and then again lower the value of equity that you obtain by the value of options that are already outstanding. It is not, since we are dealing with two separate issues. A company that has had a history of stock based compensation, but has decided to suspend using SBC in the future, will be affected by only the second adjustment, whereas a company that has never used share based compensation in the past but plans to use it in the future, will be affected only by the former. A company that has share based compensation in its past and expects to use it in the future will be affected by both adjustments.

Tesla uses stock based compensation, and its most recent annual and quarterly statements provide a measure of the magnitude.

The compensation can take the form of restricted stock or options, and the annual filing provides the cumulative effect of this share based activity. At the end of 2017, according to Tesla's 10K, the company had 10.88 million options outstanding, with a weighted average exercise price of $105.56 and a weighted average maturity of 5.30 years and 4.69 million restricted shares. The restricted shares are already included in the share count of 169.76 million shares, but the options need to be accounted for. We value the options, using a modified version of the Black-Scholes model, to arrive at a value of $2,927 million. Netting this value out of the value of equity that we obtained from the cash flows allows us to get to a corrected value per share:

The value per share, after adjusting for options, is $171.99. There is an elephant in the room in the form of a gigantic grant of 20.26 million shares to Elon Musk, with the issuance contingent on meeting operating milestones (revenues and adjusted EBITDA) and market milestones (market capitalization). The complexity of the vesting schedule on this grant makes it difficult to value using option pricing models, but the effect of this looming grant is to lower value per share today and here is why. If Tesla succeeds in growing revenues and turning to profitability, these option grants will vest, creating large expenses in the year in which that occurs and putting downward pressure on margins. In making my forecasts of future margins for Tesla, I have been more conservative at least in the early years, simply for this reason.

A Sloppy Alternative: There is an alternative approach to deal with options outstanding from past grants. They value options at their exercise value, i.e., the difference between the stock price and strike price today, and ignore out of the money options. This is called the treasury stock approach and the value of equity per share in this approach can be written as follows: Treasury Stock Value per share = (DCF value of equity + Exercise Price * # Options outstanding) / (Share Count today + Options Outstanding) By ignoring the time premium on options, this approach will over value shares today and by ignoring out of the money options, you exacerbate the problem. In the case of Tesla, using the exercise stock approach would yield the following value per share: Treasury Stock Value per share (Tesla) = ($32,124 + $105.56 * 10.88) / (169.76 + 10.88) = $184.19 The analysts who use this approach often justify it by arguing that option pricing models can yield noisy estimates, but even the worst option pricing model will outperform one that assumes that options trade at exercise value.

And Nonsensical Practices: There are two woefully bad practices, when it comes to stock based compensation, that should be avoided. The first is to just adjust the share count for options outstanding and make no other changes. In this "fully diluted" approach, you are counting in the dilution that will arise from option exercise but ignoring the cash that will come into the firm from the exercise.

- Fully Diluted Value per share = DCF value of equity / (Share Count today + Options Outstanding)

With Tesla, for instance, this approach would yield the following:

- Fully Diluted Value per share (Tesla) = $32,124/ (169.76 + 10.88) = $177.83

This approach will yield too low a value per share, and especially so if you count out of the money options as well in the denominator. The second and even more indefensible practice is to add back share based compensation to earnings to get to adjusted earnings. The rationale that is offered for doing so is that share based compensation is a non-cash expense, a dangerous bending of logic, since it allows companies to use in-kind payments (shares, services) to evade the cash flow test. Using this logic, Tesla would add back the $141.6 million they had in share-based compensation expenses to their income in the first quarter of 2018 and report lower losses. Carried into future forecasts, this will inflate future earnings and cash flows, pushing up estimated value. Since these two bad practices push value away from fair value in different directions, the only logic for their continued use is that, in combination, the mistakes will magically offset each other. Good luck with that!

Shares with different rights The Cause: Founders and families who take their companies public have always wanted to have their cake and eat it too, and one way in which they have been able to do so is by creating different share classes, usually built around voting rights. The founder/family hold on to the higher voting right shares and thus maintain control of the company, while selling off large shares of equity to the public, and cashing out. In the United States, shares with different voting rights were rare for much of the last century, primarily because the New York Stock Exchange, which was the preferred listing place for companies, did not allow them. Again, the tech boom of the 1990s changed the game, by making the NASDAQ, which had no restrictions on shares with different voting rights, an alternative destination, especially for large technology companies. The floodgates on shares with different voting rights opened up with the Google (NASDAQ:GOOGL) listing in 2004, and the Google model, with shares with different voting rights, has become the default model for many of the tech companies that have gone public in the last decade.

The Consequence: When you have different classes of shares, with different voting rights, you have two effects on value. The first is a corporate governance effect, since changing management becomes much more difficult, and that can affect how you value and view badly managed firms. The second is a unit problem, since a voting right share and a non-voting right share represent different equity claims and cannot be treated as having the same value. Thus, you can no longer divide the aggregate value of equity by the total number of shares outstanding.

The Right Response: When valuing firms with different voting rights, you have to deal with it in two steps. When valuing the firm, you have to incorporate the fact that changing management is going to be more difficult to do in your estimates. Thus, if you firm borrows no money (even though it can lower its cost of capital by moving to an optimal or target debt ratio fo 40%), you should leave the debt ratio at zero rather than change it. This will lower the value that you estimate for the operating assets and equity in the firm. Once you have the value of equity, you will have to make a judgment on how much of a premium you would expect the voting shares to trade at, relative to non-voting shares, in one of two ways. In the first, you can look at studies of voting shares in publicly traded companies in the US and Europe, which find a premium of between 5-10% for voting shares, and use that premium as your base number. In the second, you can use an approach that uses intrinsic valuation models to estimate the premium, which I describe in my paper on valuing control . Once you have the estimate, you can use algebra to complete your estimate of value per share. Value per non-voting share = Aggregate Value of Equity/ (# Non-Voting Shares + (1+ Voting Share Premium) # Voting Shares) For example, if the value of equity is $210 million, there are 50 million non-voting shares and 50 million voting shares and the voting share premium is 10%, your value per non-voting share will be: Value per non-voting share = 210/ (50+ 1.1*50) = $2.00/share Value per voting share = $2.00 (1.10) = $2.20/share

The Bottom Line I know that some of you will view this post as nit-picking, but you will be surprised at how much of an effect on value you can have by not being careful about share count. Those of you who use multiples (PE, EV/EBITDA) may be secretly happy that you don't have to deal with the issues of share count, since you don't do discounted cash flow valuations. Unfortunately, that is not true. Dilution, share based compensation and shares with different rights are just as much an issue when you compare multiples across companies, and ignoring them or using short cuts (like full dilution) will only skew your comparisons and lead to mis-pricing stocks. I would suggest four general rules:

- Aggregate versus Per-share numbers: Given how dilution and options can play havoc with share count, it is better to use aggregate than to use per share numbers, in valuation and in pricing. Thus, to obtain PE, divide the market capitalization of the company by its total net income, rather than price per share by earnings per share.

- When SBC is rampant, control for differences: If the use of restricted stockand options vary widely across sector, you need to control for those differences when comparing pricing in the sector. If you do not, companies that have large option overhangs will look cheap, relative to those that do not.

- Don't use SBC adjusted earnings: Adjusting earnings and EBITDA, by adding back stock based compensation, is an abomination, used by desperate companies and analysts to show you that they are making money, when they are not even close. Don't fall for the sleight of hand.

- With forward multiples, check on and control for dilution: Analysts, when valuing young companies, often divide today’s market capitalization or enterprise value by expected revenues or EBITDA in the future. The dilution that will be needed to get to future EBITDA has to be brought into the equation.

Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.