“Big Short” Contrarian Has A New Target

Contrarian Outlook | Sep 16, 2019 05:29AM ET

You’ve probably heard of Michael Burry.

Played by Christian Bale in the film The Big Short, Burry famously made nearly a billion dollars betting against the housing bubble in the 2000s.

Now this legendary contrarian has a new target: funds.

He’s mostly panning passive exchange-traded funds (ETFs), but he’s got a lot of disdain to go around. In a recent interview with Bloomberg, Burry said that many funds are forming a bubble that’s getting bigger, whether they’re “open-end, closed-end or ETF.”

As a big fan of closed-end funds (CEFs)—including the top-quality 8.6%-yielder I’ll show you shortly—this comment stopped me. But if you dig a bit deeper, you realize that Burry’s target isn’t CEFs, but a particular flavor of funds that have attracted an almost religious devotion in recent years.

The Next “Big Short”?

Burry goes on to explain that the problem is limited to passive index funds—a low-fee investment that many advisors recommend. Burry claims these funds have a “dirty secret.”

Before I go further, let me be clear that I’m no fan of passive funds, either—but for a different reason than Burry: in many cases, passive index funds underperform actively managed CEFs, especially in less familiar areas like municipal bonds or preferred stocks, where professional management can make a real difference.

This is one dirty little secret of passive funds: despite their lower fees, their returns are actually worse than the alternatives!

But Burry is more worried about liquidity. He contends that many illiquid stocks that passive funds are required to buy and sell could easily crash in a market panic. Simply put, if all index funds are trying to sell the same stock at the same time, prices will collapse in a vicious cycle that could trigger individual investors to panic sell, making the problem worse.

CEFs: 7%+ Dividends Made for a Panic

What’s getting lost here is that this kind of scenario is exactly what CEFs are built for. To see how, let’s consider how these unique funds are put together.

In the case of an ETF, the fund will grow or shrink in size as investors bring money in or out, while CEFs have a set amount of shares—meaning new money in or out will change the market price of the CEF, but not the total number of shares in the fund. This is important, because an ETF is required to sell its investments when shareholders sell their stocks, but CEF managers aren’t. They can ignore the panicking market, hold their stocks and wait for a recovery.

Without being forced to sell at a loss, CEFs can avoid the short-term panicky markets that Burry feels will cause ETF losses to compound on each other.

There’s another advantage to the CEF structure: the opportunity for contrarians to get in at a huge discount.

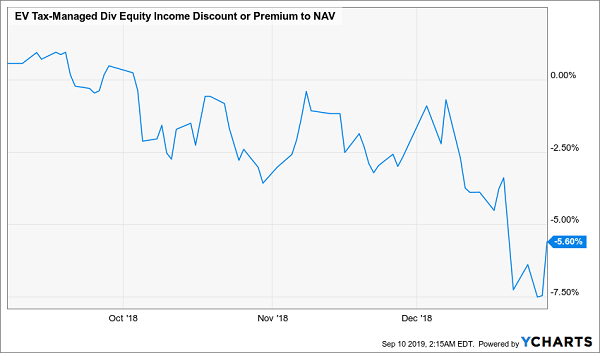

Take, for instance, the Eaton Vance Tax-Managed Dividend Equity Income Fund (NYSE:ETY), a stock fund that, along with all funds in late 2018, saw its portfolio (its net asset value, or NAV) fall in value as we hit the first bear market in a decade.

Because ETY is a CEF, it could (and did) hold its assets—large-cap names like Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT), Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) and Verizon Communications (NYSE:VZ)—even as investors were selling their stakes in the fund. During this decline, the fund’s NAV fell 12%, roughly in line with the broader market. However, panicky retail investors’ selling pressure caused the fund’s market price to sink further than its NAV. As a result, the fund stopped selling at around the value of its portfolio and began selling at a discount to its NAV:

A Sale Suddenly Appears

Investors who saw this as an opportunity and bought in when the discount was at its widest were swiftly rewarded with a huge, fast profit that was well ahead of the return on the benchmark SPDR S&P 500 ETF:

ETY’s Sudden Gift to Contrarians

With a 31% total return in just half a year, ETY crushed the S&P 500, despite investing in many of the same companies. Investors who bought in when the market was fearful were able to profit on the market’s irrational sell-off, thanks to the CEF’s discount to NAV, without worrying they were getting into the forced-selling trap Burry is warning about.

That isn’t ETY’s only benefit. The fund also pays a huge 8.5% dividend yield, well over four times as much as SPDR S&P 500 (NYSE:SPY). That’s another reason why CEFs are a powerful tool in a downturn: if you need income, the best ones will keep delivering, so you won’t be forced to sell at a loss to pay the bills.

Forget ETY: These Are the 8%+ Dividends You MUST Buy Now

Too bad ETY trades at a 0.42% premium to NAV today, so we’ll have to rely on the market finding its way higher if we want to tap more price gains from this fund.

And I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to leave my nest egg to the whims of the average investor.

That’s why I recommend 5 other “hidden” CEFs I want to show you now. This quintet yields 8%, on average, and some pay even more, like the top fund on my list, which throws off an amazing 9.3% payout now.

I say these CEFs are “hidden” because Wall Street’s biggest fund firms are throwing all their marketing cash at “dumb” ETFs like SPY and totally ignoring CEFs.

It’s no wonder. If more people knew about the huge cash payouts on offer in CEF-land, they might never buy another ETF again!

And here’s the kicker: in addition to those growing 8% dividends, these 5 funds trade at ridiculous discounts to NAV—so much so that I expect 20%+ price upside from each of them in the next 12 months!

Heck, many of my 5 CEF picks have done even better than that already—like that 9.3%-yielder I just mentioned. Check out the drubbing it’s laid on the S&P 500 in the last two decades:

Pick No. 1 Soars 743%—and It’s Still Cheap!

And get this: despite that 743% gain, this one trades at a 9% discount to NAV, even though it’s traded at a premium many times in the past.

That’s our cue to climb aboard and get set for another 20%+ in price gains!

Disclosure: Brett Owens and Michael Foster are contrarian income investors who look for undervalued stocks/funds across the U.S. markets. Click here to learn how to profit from their strategies in the latest report, "7 Great Dividend Growth Stocks for a Secure Retirement ."

Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.