‘A Flawed Idea’: Why a BRICS Currency Is Overrated and Unlikely to Work

Adem Tumerkan | May 01, 2023 01:58AM ET

Over the last month, I’ve seen a wave of hysteria regarding ‘de-dollarization’ and the formation of a BRICS currency.

Headlines like “Argentina Ditching Dollar” and “Saudi Arabia Moving Towards Yuan” and “Brazil Declares War On Dollar” have spread like a fire.

But I don’t buy the hype.

Why?

Because there are massive imbalances within the BRICS. Such as – they all essentially run current account surpluses. Have extremely high domestic savings rates. And would depend on the Chinese economy and the yuan as the backbone for a currency bloc.

Let’s be clear – BRICS is simply an eroding growth engine in China. A golden goose that’s never laid an egg (but has potential) in India. And three anemic commodity producers in Russia, Brazil, and South Africa.

Now, it’s not impossible for a BRICS currency to happen. But it would require a significant amount of pain that these countries don’t want to endure.

Keep in mind this is a complex macroeconomic topic (although grossly underrated). And I don’t plan to cover everything. But these are important topics that no one ever seems to discuss regarding a BRICS currency.

So, let’s take a closer look at all this. . .

Almost All of BRICS Run Current Account Surpluses, Thus Depending On Western (Mostly U.S.) Deficits

In economics, it’s generally taught that a country running a current account surplus (aka exporting more goods and savings than it imports) is a ‘good’ thing. And that a deficit (importing more goods and savings than it exports) is ‘bad’.

But I don’t look at things so black and white. Especially in markets.

Instead, it’s just a balancing act. Meaning a surplus somewhere is a deficit elsewhere (and vice versa).

And currently, almost all BRICS are running huge current account surpluses (with India quickly moving towards one).

Meanwhile, the U.S. and U.K. run large current account deficits to match these.

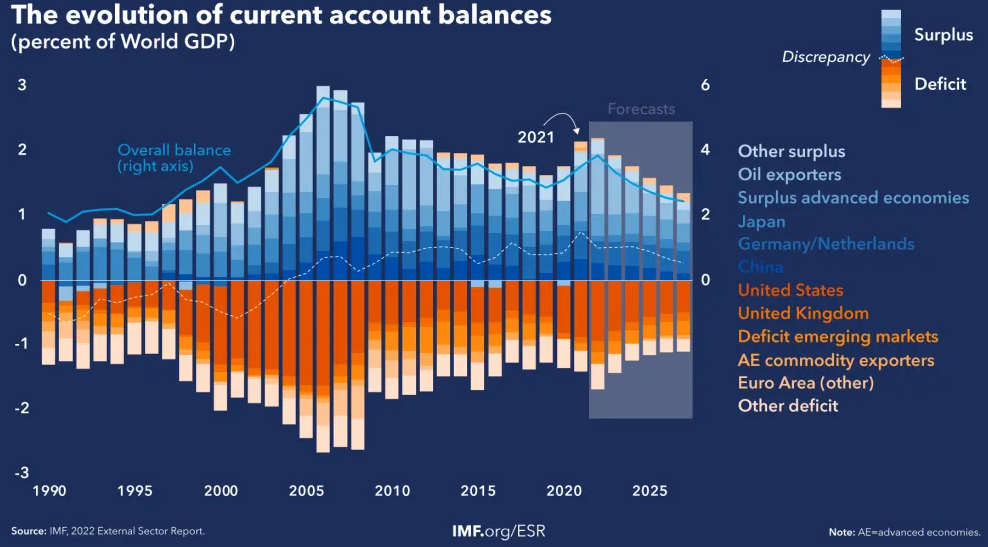

For perspective, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently noted the evolution of global current accounts as a percentage of world GDP after the Russia-Ukraine war began.

And as you can see, not only do they balance. But have actually widened since 2020.

Seems ‘good’ for BRICS, right?

Well, not so fast.

These current account surpluses also indicate that BRICS (and Germany and Japan) have extremely unbalanced economies. Meaning they aren’t consuming what they produce, thus needing to export the rest abroad.

Or – put it another way – these current account surpluses show us that BRICS have low domestic demand. And thus depend on the Western economies to import their glut of goods and savings for growth.

These chronic BRICS surpluses indicate two things:

1. BRICS has very low consumption capacity because of weak household incomes.

Just take a look at the World Bank’s household financial consumption expenditures (HFCE – aka consumer spending) at the end of 2021.

There’s a massive gap between consumer spending in the BRICS and the U.S.

U.S. consumer spending is nearly $16 trillion – which is 50% more than all of BRICS put together ($10.8 trillion).

The BRICS just don’t have enough consumer purchasing power to absorb all of what they produce and depend on exports.

Thus if it wasn’t for the deficits (excess buying) in the West, these economies would drown in deflation and unemployment as all their unconsumed goods sit idle.

Or – putting it plainly – they depend on their exports to the West for growth and foreign reserves at the expense of their own anemic consumers.

2. The BRICS nations (most of them) have excessively high domestic savings rates relative to GDP.

Note that other major current account surplus nations – such as Germany, Japan, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia – also have very high savings rates.

Germany is at 29%. Japan is at 29%. South Korea is at 35%. And Saudi Arabia is at 38%.

These numbers dwarf the U.S.’s 17% and U.K.’s 15% savings rates.

Keep in mind that households can only do two things with income – dissave (consume) or save (not consume).

And when there are more savings, it means that this excess must be exported for more yield abroad.

In fact, many of these BRICS and emerging economies depend on high savings to fuel their export growth.

As Michael Pettis pointed out, the high savings growth model “seems to be driven mainly by growth in savings, which provides the cheap capital that drives investment, which in turn drives productivity gains” and thus exports.

This is also known as the Gerschenkron model theory – named after economist Alexander Gerschenkron.

He wrote that the more backward an economy is at the outset of development, the more likely certain conditions will occur.

These include – government-controlled banks that channel physical and human capital into specific industries. A focus on producer goods rather than consumer goods. Emphasis on agricultural/commodity sectors as a market for new domestic industries will be small. And more capital-intensive production rather than labor-intensive production (focus on capital for returns rather than labor efficiency).

Sound familiar? This is what China, Russia, Brazil, and even Japan have done to an extent.

Thus the high savings turn into less domestic consumption, which creates a larger current account surplus. And more reserves in state coffers.

And what do they do with these dollar reserves? They buy U.S. bonds as collateral (yield) and also use it to keep their currencies weak against the dollar – making sure export growth continues.

But most importantly, it’s also shown to be historically very difficult to rebalance from a high-savings and export economy into domestic demand driven because of special interest groups in the heavily subsidized capital-and-export sectors.

And this brings us to our next part. . .

Japan: A Case Study Showing How Difficult It Is To Rebalance An Economy From Supply-Focused And Into Domestic Demand.

Japan grew into a manufacturing powerhouse after world war two ended.

They followed most of the Gerschenkron growth model and ran chronically large current account surpluses focusing on global demand rather than depending on domestic consumption.

For context: in the late-1980s, Japan was a major export-driven economy. In fact, exports as a percentage of GDP were a staggering 15% in 1984.

But in 1985, there was the signing of the Plaza Accord – aka the attempt to devalue the U.S. dollar against the Japanese Yen and German Mark – to correct trade imbalances.

Why? Because a weaker dollar made U.S. manufacturing relatively more competitive. And a stronger Yen meant greater imports into Japan.

Thus Japan’s currency appreciated over 40% relative to the dollar between 1985 and 1990.

This surge in the Yen greatly impacted Japan’s economy.

For starters, it hurt their exports – which sank to just 9% of GDP in 1989. It also led to surging household debt (rising from 52 to a staggering 68 as a percentage of GDP in just five years) as the stronger Yen made imports rise. And it also helped push the Japanese bubble economy into debt deflation (where it’s essentially remained for the last 30 years).

But here’s where things get interesting. . .

In 1986, the Japanese Prime Minister essentially formed a ‘brain trust’ to try and change Japan’s economy from export-driven to demand-driven.

What they released was called the Maekawa Report – named after Haruo Maekawa, the former head of the Bank of Japan.

This report essentially proposed economic reforms in Japan, designed to make the living standards higher and reduce the chronic current account surpluses.

And for this to happen, Japan must switch from export-oriented growth into a domestic-service-fueled economy.

It also noted a focus on more consumer spending rather than savings. And that a stronger Yen would fuel imports, and thus increase the Japanese standard of living.

It was Japan’s attempt to plant the framework for an economic rebalancing.

But – as expected – it was extremely unpopular and opposed by the Liberal Democrats and special interest groups (such as the powerful export and manufacturing sectors). Thus the report never materialized into anything. And thirty years later, they’re still a stagnant economy running chronic current account surpluses.

This is important since Japan’s economy is a case study for China if it ever plans to rebalance itself.

The similarities between the two nations are glaring – such as the weak domestic consumer, eroding demographics, excessive institutional debt, and malinvestment.

But if China plans to lead a BRICS currency bloc, it will have to rebalance. . .

How A BRICS Currency Could Work – And It’ll Require A Lot From China That They Don’t Want To Give

While there’s a lot of clamoring by BRICS to challenge the dollar, I believe there are – at a fundamental level – two big problems with a BRICS currency.

First Issue – all BRICS run current account surpluses. Meaning they must export their excess abroad (as detailed above) to the West.

Or said another way, if they want to cut out the dollar – and essentially the West – who will run the deficits required to absorb the BRICS excesses?

They can’t all run surpluses with each other (remember it must balance).

So from a scale perspective, it must be China to absorb their excess – making them fully reliant on Beijing.

But, China doesn’t seem to want to rebalance its own economy and export yuan abroad en masse to subsidize BRIS exports.

In fact, China recently doubled down on export growth since it can’t get any consumption going domestically.

For instance – in February 2023 – China’s current account surplus hit a 14-year high – which was 32% larger than in 2021. And the most since 2008.

Meanwhile – as Brad Setser noted – China’s manufacturing trade surplus as a percentage of GDP is now over 10%. Also back at 2008 levels.

This means that the world’s effectively supplying over 10% of China’s demand which they can’t generate domestically.

And to highlight the power the U.S. consumer has for carrying global growth, the U.S. current account deficit (what it imports in excess) is more than the other major deficit nations put together.

In fact – even before COVID (2019) – the U.S. current account deficit was roughly the same as the next 19-deficit-running nations.

That’s an enormous number of imports and consumption due to the U.S. and means that the U.S. alone is creating demand for nearly $1 trillion (as of 2022) in foreign goods.

Now, is it prudent for the U.S. to consume so much more and suffer increased debt burdens?

No. But U.S. deficits keep dollar liquidity flowing globally (I’ve written about this in-depth before – read here).

And this is a huge reason the dollar has proliferated into the global economy.

Because when the U.S. imports more than it exports, it’s selling dollars and collateral (bonds). Those exporters (buying dollars) then have the cash to build as reserves or invest or spend.

But China, the world’s largest surplus-running nation, doesn’t net export yuan (since they’re selling more than buying). Thus no one can get the very yuan needed to buy goods.

To put this into perspective – according to SWIFT – the yuan only makes up less than 2.5% of global payments. That’s nothing compared to the dollar’s 40% share and the euro’s 36%.

To change this, it would require China to run huge deficits instead to supply the world with yuan liquidity and bonds. And Beijing doesn’t seem willing to do that.

Thus if BRICS want to cut out the U.S. and the dollar, it will come at an extremely expensive cost in their own export economies. And I don’t believe they have the political stomach for that.

Second Issue – a BRICS currency requires all economies to be pegged to one currency and its respective monetary policy.

In a peg system, there must be an anchor economy or system that maintains interest rates and liquidity.

And historically speaking, when countries want to form a currency bloc, they peg to the most economically powerful country with low inflation rates.

For example, when the euro and the European Central Bank (ECB) were created in 1998-99, it was modeled after the German Bundesbank (their central bank at the time) as Germany was the powerhouse of Europe.

This meant that any and all eurozone members (there are 20) using the euro must abide by the policies set by the ECB.

This has caused serious issues between Germany and the rest of the eurozone. Such as the ECB aggressively easing policies to support weaker members at the expense of German savers.

Or like when Greece needed two huge bailouts back in 2010-2012, they were at the mercy of the ECB and Germany who gave them loans in return for forced Greek austerity measures.

This meant that Greece and other indebted euro nations were forced to suffer deep recessions. And further austerity made it worse – even though Germany and others were growing.

If Greece had its own central bank and its former currency – the drachma (pre-2001) – they could’ve avoided ECB policies imposed on them and increased deficits and liquidity instead.

This is a core problem when you lump different economies with different growth agendas and different inflation rates altogether.

So – if a BRICS currency was ever formed – it would most likely be based on China’s monetary system.

But what if China goes into an overheating cycle and looks to tighten liquidity? Yet Brazil was in a recession?

Brazil would want lower interest rates to stimulate while China wants higher rates to cool down. And this would cause a conflict of interest between them.

Thus it wouldn’t make sense for the BRICS to have a single currency as they’re so different. And all would effectively be tethered to China’s boom-bust cycle.

It seems more likely they would instead peg their own local currencies to the yuan in a semi-peg system. Meaning their currencies can trade within an XYZ band against the yuan.

But the same issues remain.

If China raises interest rates, strengthening the yuan and draining excess liquidity, all others in BRICS would also have to raise interest rates to maintain the peg (otherwise it will break).

If they have built up yuan reserves, then they can raise interest rates while selling their yuan to buy their own currencies (maintain the peg).

But they’d be bleeding reserves in doing so.

Also, what if one peg is set too high for an economy or set too weak?

For example, if the Russian ruble is pegged at a higher rate than its economy can justify, it will constrict exports, raise imports, and cause chronic deficits – eventually leading to the peg breaking.

Meanwhile, if the South African dollar is pegged at a lower market rate. It will lead to increased exports, but costlier imports and weaker standards of living.

Such a peg system between diverse economies and political agendas could create unfair trade advantages between BRICS and lead to resentment (as we’ve seen in the Eurozone).

In Conclusion

The balance of payments between the U.S. (deficit) and the BRICS (surplus) doesn’t seem to get a lot of attention.

But it’s absolutely critical to understand how these economies function.

The BRICS have extremely anemic consumers and remain export driven. Dumping their goods on the global markets (mostly U.S.).

If the U.S. tomorrow said, “We are going to balance our budget and slash deficits,” the BRICS economies would feel a tremendous decline in growth and liquidity.

In fact, these countries hoard dollar reserves to make sure their currencies remain weak against the dollar (keeping the dollar stronger) to promote exports.

For perspective – in a free market system – all the inflows of dollars into China would raise the yuan’s value and decrease the dollar’s value. Thus creating more import capacity in China and subsequently more exports from the U.S.

But we haven’t seen that.

Instead, the U.S. dollar has soared 30% in the last 15 years relative to foreign currencies. Even in the face of massive deficits and huge Federal Reserve easing.

Meanwhile, the Chinese yuan has actually decreased in value against the dollar in the same period – even with above-trend growth and huge surpluses.

That’s because these export economies – such as China – use a form of ‘currency mercantilism’ – aka hoarding dollar reserves and use aggressive government subsidies for exports.

And it has come at the cost of their consumers (domestic demand).

But as we learn from history – there is a thing called diminishing returns for growth. And China has hit that wall in its current economy (just as Japan did before thirty years ago).

Thus if BRICS is ever serious about actually de-dollarizing, they will have to completely rebalance their economies.

This means a focus on allowing their currencies to strengthen (promoting imports). Stimulate domestic consumers (lower the savings rates and spur household borrowing). And stomach-increasing deficits.

But as I noted above about Japan post-1985 – it’s extremely difficult to do and has its own set of problems.

Now, it could happen. But it doesn’t appear China wants to trade their export economy and deal with the painful rebalancing to subsidize BRIS and even U.S. manufacturing.

We hear many pundits say, “How long can the U.S. deficits remain?”

I would flip that question and ask, “How long can the global surplus-running nations remain?”

Since 2012, three of the four largest economies – China, the Eurozone, and Japan – all run net-current account surpluses. Indicating extremely anemic domestic consumers. And thus why they’re all stuck between slowing growth and relative deflation.

This has put ever-greater pressure on the U.S. and its consumer to drive global consumption.

But it’s clear that this absorption of the rest of the world’s gluts has come with negative effects on consumers long-term. (I’ve written more about this ‘debt-trap’ – read here).

So until we see any of this change, I believe the BRICS currency idea is flawed.

As always, only time will tell.

***

*NOTE: I know this is a very complicated topic and that I just covered a fraction of it. So I plan to publish more on this in time. But for more insight, I highly recommend the book ‘Trade Wars Are Class Wars’ by Michael Pettis and Mathew Klein.

Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.