3 Colliding Macro Trends Set to Put U.S. Economy to the Test

Michael Ashton | Aug 03, 2023 04:02AM ET

It’s ironic that I had planned this column a couple of days ago and started writing it yesterday because the very concerns I talk about below are behind the overnight news that Fitch is lowering its long-term debt rating for US government bonds one notch to AA+. That matches S&P’s rating (Moody’s is still at Aaa).

Let me say at the outset that I am not at all concerned that the US will renege on its bonds in the classic sense of refusing to pay. Classically, a government that can print the money in which its bonds are denominated can never be forced to default. It can always print interest and principal.

Yes, this would cause massive inflation, and so would be a default on the value of the currency. Again classically, this is no decision at all. However, it bears noting that there may be some cases in which the debt is so large that printing a solution is so bad that a country may prefer default so that bondholders, and not the general population, take the direct pain. I don’t think this is today’s story or probably this decade’s story. Probably.

But let’s get back to what I intended to talk about.

Here are three big-picture trends that are tying together in my mind in a way that bothers me:

- Large and increasing (again) federal deficits

- An accelerating trend toward onshoring production to the US

- The Federal Reserve continuing to reduce its balance sheet

You would think that two of the three of those are unalloyed positives. The Fed removing its foot from the throat of debt markets is a positive, and re-onshoring production to the US reduces economic disruption risks in the case of geopolitical conflicts and provides high-value-added employment for US workers. And, of course, all of that is true. But there’s a way these interact that makes me nervous about something else.

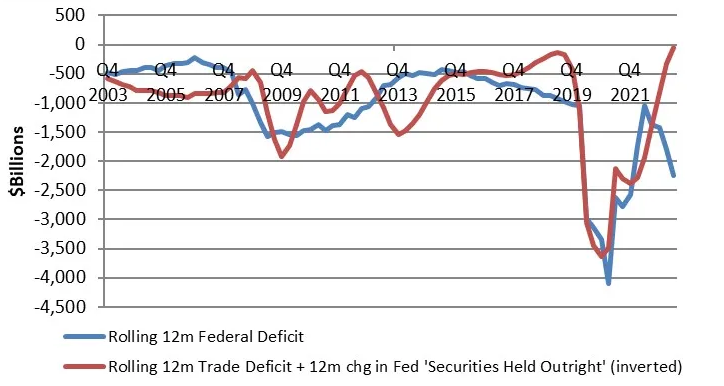

This goes back to the question of where the money comes from to fund the Federal deficit. I’ve talked about this before. In a nutshell, when the government spends more than it takes in, the balance must come from either domestic savers or foreign savers. Because “foreign savers” get their stock of US dollars from our trade deficit (we buy more from Them than They buy from us, so we send them dollars on net which they have to invest somehow), looking at the flow of the trade deficit is a decent way to evaluate that side of the equation. On the domestic side, savings come mainly from individuals and, over the last 15 years or so, from the Federal Reserve. This is why these two lines move together somewhat well.

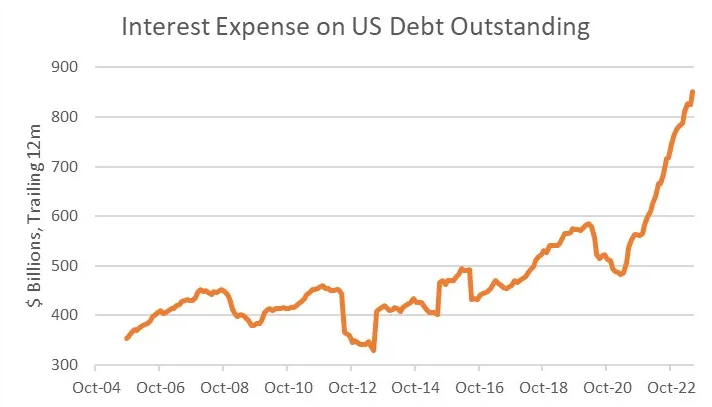

Now, you’ll notice that in this chart, the red line has gone from a deep negative to basically flat. The trade deficit has improved (shrunk) by about a trillion since last year, and the Fed balance sheet has shrunk by 800bln or so. But, after improving for a bit, the federal deficit is now moving in the wrong direction, growing larger again even as the economy expands and creating a divergence between these lines. This is happening partly, although not entirely, because of this trend, which will only get worse as interest rates stay high and debt is rolled over at higher interest rates:

The problem in the first chart above is the gap that’s developing between those two lines. Because the difference is what domestic private savers have to make up. If you’re not selling your bonds to the Fed, and you’re not selling your bonds to foreign investors who have dollars, you have to be selling them to domestic investors who have dollars. Domestic savers are, in fact, saving a bit more over the last year (they saved a LOT when the government dumped cash on them during COVID, which was convenient since the government needed to sell bonds).

So here’s the problem.

The big-picture trend of big federal deficits does not appear to be changing any time soon. And the big-picture trend of re-onshoring seems to be gathering momentum. One of the things that re-onshoring will (eventually) do is reduce the trade deficit since we’ll be selling more abroad and buying more domestic production. A smaller trade deficit means fewer dollars for foreign investors to invest. The big-picture trend of the Fed reducing its balance sheet will eventually end, of course, but for now, it continues.

And that means that we need domestic savers to buy more and more Treasuries to make up the difference. How do you get domestic savers to sink even more money into Treasuries? You need higher interest rates, especially when inflation looks like it is going to be sticky for a while. Moreover, attracting more private savings into Treasury debt, instead of, say, corporate debt or equity or consumer spending, will tend to quicken a recession.

I don’t worry about recessions. They are a natural part of the business cycle. What I worry about is breakage. Feedback loops are a real part of finance, and out-of-balance situations can spiral. The large deficits the federal government is generating, partly (but only partly) because of prior large deficits, combined with the fact that the Fed is now a seller and not a buyer, and the re-onshoring trend that is slowly drying up the dollars we send abroad, creates a need to attract domestic savers and the only way to do that is with higher interest rates. Which, ultimately, raises the interest cost of the debt, which raises the deficit…

There are converging spirals, and there are diverging spirals. If this is a converging spiral, then it just means that we settle at higher interest rates than people are expecting, but we end up in a stable equilibrium. If this is a diverging spiral, it means that interest rate increases could get sloppy, and the Fed could be essentially forced to stop selling and start ‘saving’ again. Which in turn would provide support for inflation.

None of the foregoing is guaranteed to happen, but as an investment manager, I get paid to worry. It seems to me that these three big macro trends aren’t consistent with stable interest rates, so something will have to give.

One of those things was the country’s sovereign debt credit rating. The Fitch move seems sensible to me, even if that wasn’t the original point of this article.

Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.