Inflation has slowed sharply in the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). From nearly 2.5% in fall 2012, it dropped to 1.2% in April 2013, well below the ECB’s official 2% target. This is the lowest inflation rate in three years. For the most part, the easing trend is due to energy prices: with the decline in oil prices, gas and household fuel bills have eased. The ECB also pointed out temporary factors such as the calendar effect of the Easter holiday, which is also a way of minimizing the phenomenon. According to the ECB, inflation expectations are still “well anchored”. Moreover, “with the decline in interest rates, the risks to price stability are generally well balanced in the medium term”.

Subdued trend in prices in southern Europe…

Is this a case of denying reality? In the eurozone, there is nothing anecdotic about the widespread easing of inflation, and everything suggests this trend will continue. Core inflation, which excludes the most volatile components like energy and food, is clearly slowing. For the 17 eurozone members, core inflation is holding to a slope of 1% a year, and in France, inflation is virtually flat at 0.4% a year. It is also important to note that VAT increases have maintained inflation artificially high (in Spain, for example). Once these effects dissipate, inflation will probably step downwards. Excluding fiscal effects, consumer price inflation is virtually non-existent in the southern EMU countries. From a broader perspective, this inertia is confirmed by GDP deflators.

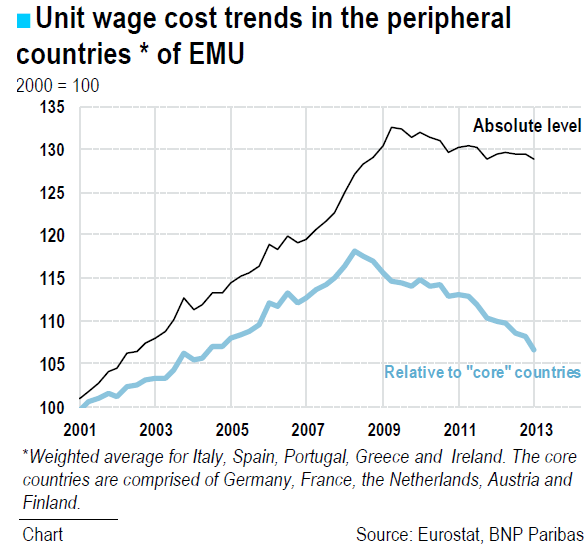

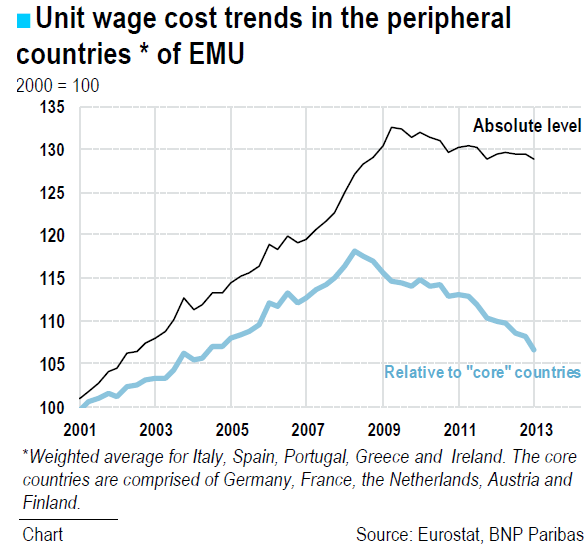

How could things be otherwise? Deprived of exchange rate tools, the peripheral countries of the eurozone have turned to internal deflation policies over the past three years to orchestrate adjustments. Costs and prices are under constant pressure, whether from “structural” reforms (i.e. lowering the minimum wage and welfare benefits) or simply through rising unemployment. The chart shows that since 2009, unit wage costs have declined in the peripheral countries of EMU, not only with respect to the rest of the eurozone, but also in absolute terms, which is unheard of.

And that is not all. It is well known that the interest rate cut advocated by the ECB and justified by the “low risk” for price stability has little impact on financing conditions in the southern countries of the eurozone. In these countries, the average interest rate on corporate loans is still two to three times higher than in the rest of EMU: about 5% to 6% Spain and Portugal, compared to 2% in France4.

The main problem with EMU monetary policy is that a good part of the eurozone – notably the most heavily indebted countries– is left to struggle with excessively high real interest rates. In the south, credit aggregates are not just slowing: they are plunging dangerously. Under these conditions, it is hard to imagine a “stable” inflation outlook.

The main problem with EMU monetary policy is that a good part of the eurozone – notably the most heavily indebted countries– is left to struggle with excessively high real interest rates. In the south, credit aggregates are not just slowing: they are plunging dangerously. Under these conditions, it is hard to imagine a “stable” inflation outlook.

… spreading northwards

Having slashed costs, the peripheral countries of the eurozone are experiencing little inflationary pressures, and have become serious competitors on export markets. Although France no long has to put up with devaluation of the peseta or escudo, its export sales are not growing nearly as fast as those in Spain or Portugal, especially since these countries are not big consumers. Faced with more competitive partners that are less inclined to spend, numerous French companies have been forced to squeeze prices. This undoubtedly explains why core inflation is so low in France. Germany has been relatively sheltered from this constraint thanks to more solid competitive positions that are less sensitive to prices. Yet inflation in Germany is slowing, too.

To avoid any deflationary risks in the southern part of the eurozone, it would be better to offer more favourable financing conditions, notably for medium to long-term instruments. Having exhausted the possibility of reducing key rates, and since euro bonds are no longer on the agenda, several other solutions are being explored, such as developing an asset-backed securities market based on corporate loans. Yet it will take time to set this up. In the meantime, the ECB could still lower yields by purchasing debt instruments, that is if it ever makes up its mind to do so.

BY Jean-Luc PROUTAT

Subdued trend in prices in southern Europe…

Is this a case of denying reality? In the eurozone, there is nothing anecdotic about the widespread easing of inflation, and everything suggests this trend will continue. Core inflation, which excludes the most volatile components like energy and food, is clearly slowing. For the 17 eurozone members, core inflation is holding to a slope of 1% a year, and in France, inflation is virtually flat at 0.4% a year. It is also important to note that VAT increases have maintained inflation artificially high (in Spain, for example). Once these effects dissipate, inflation will probably step downwards. Excluding fiscal effects, consumer price inflation is virtually non-existent in the southern EMU countries. From a broader perspective, this inertia is confirmed by GDP deflators.

3rd party Ad. Not an offer or recommendation by Investing.com. See disclosure here or remove ads.

How could things be otherwise? Deprived of exchange rate tools, the peripheral countries of the eurozone have turned to internal deflation policies over the past three years to orchestrate adjustments. Costs and prices are under constant pressure, whether from “structural” reforms (i.e. lowering the minimum wage and welfare benefits) or simply through rising unemployment. The chart shows that since 2009, unit wage costs have declined in the peripheral countries of EMU, not only with respect to the rest of the eurozone, but also in absolute terms, which is unheard of.

And that is not all. It is well known that the interest rate cut advocated by the ECB and justified by the “low risk” for price stability has little impact on financing conditions in the southern countries of the eurozone. In these countries, the average interest rate on corporate loans is still two to three times higher than in the rest of EMU: about 5% to 6% Spain and Portugal, compared to 2% in France4.

The main problem with EMU monetary policy is that a good part of the eurozone – notably the most heavily indebted countries– is left to struggle with excessively high real interest rates. In the south, credit aggregates are not just slowing: they are plunging dangerously. Under these conditions, it is hard to imagine a “stable” inflation outlook.

The main problem with EMU monetary policy is that a good part of the eurozone – notably the most heavily indebted countries– is left to struggle with excessively high real interest rates. In the south, credit aggregates are not just slowing: they are plunging dangerously. Under these conditions, it is hard to imagine a “stable” inflation outlook.

3rd party Ad. Not an offer or recommendation by Investing.com. See disclosure here or remove ads.

… spreading northwards

Having slashed costs, the peripheral countries of the eurozone are experiencing little inflationary pressures, and have become serious competitors on export markets. Although France no long has to put up with devaluation of the peseta or escudo, its export sales are not growing nearly as fast as those in Spain or Portugal, especially since these countries are not big consumers. Faced with more competitive partners that are less inclined to spend, numerous French companies have been forced to squeeze prices. This undoubtedly explains why core inflation is so low in France. Germany has been relatively sheltered from this constraint thanks to more solid competitive positions that are less sensitive to prices. Yet inflation in Germany is slowing, too.

To avoid any deflationary risks in the southern part of the eurozone, it would be better to offer more favourable financing conditions, notably for medium to long-term instruments. Having exhausted the possibility of reducing key rates, and since euro bonds are no longer on the agenda, several other solutions are being explored, such as developing an asset-backed securities market based on corporate loans. Yet it will take time to set this up. In the meantime, the ECB could still lower yields by purchasing debt instruments, that is if it ever makes up its mind to do so.

BY Jean-Luc PROUTAT

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.